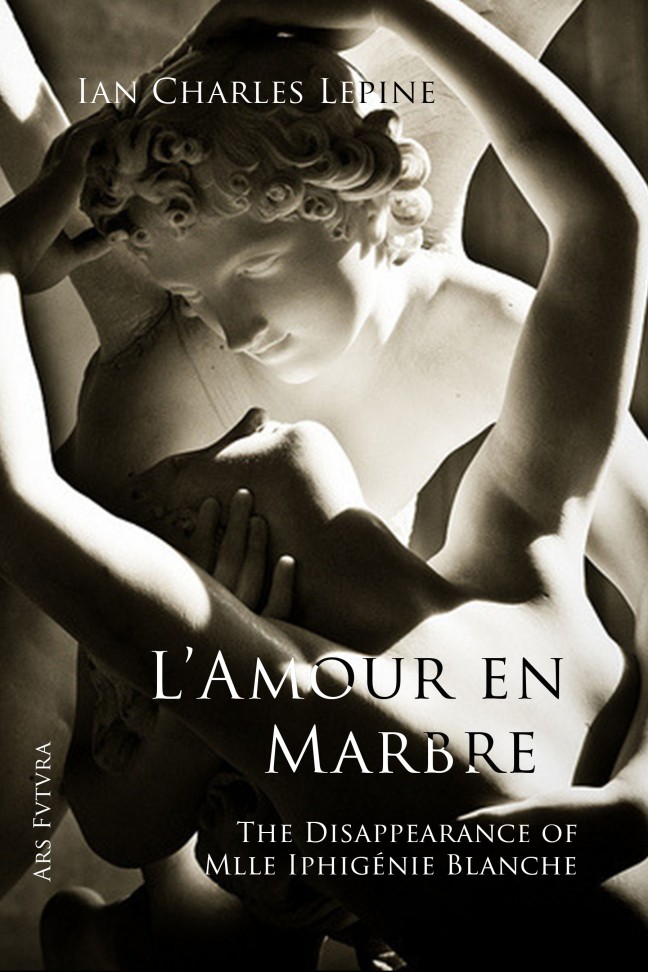

This is a free sample of my new murder mystery novel, L’Amour en Marbre: The Disappearance of Mlle Iphigénie Blanche. If you are interested in a signed copy, do message me at iancharleslepine@gmail.com

Chapter One: The End

Love is a precious flower that grows slowly, but, between some people, in the right hearts, in the right circumstances, it grows in an instant; like a moonflower, it blooms in a second and its petals are all the more wonderful for the vehemence of their miracle. But early springs mean early winters; and sudden joys, immediate sorrows.

Losing someone you love is worse than losing a limb, for someone’s love covers your entire body; for they have kissed every inch of your skin, and, therefore, when they’re gone, you feel flayed, as though your emotions were exposed, out in the open, asphyxiating air; you feel a phantom limb pain, but the limb that you have lost is, of course, your entire self.

Time passes but some wounds are too great to ever be covered by years or scars. Wounds that are the size of oneself can never heal: what’s there to heal, when you are like a human hole in the universe? or rather losing someone you love is like having a hole in the floor of your mind. You don’t learn to walk across it; you learn to walk around it, you train yourself not to look at the pictures of the other person in the living room, because that would be almost as painful as taking them down.

What could he do but make the hole literal? To turn the metaphor into a gaping wound? Wholly, holily. He walked towards the bookcase and retrieved his Bible. That, if nothing else, would hold the answer. Not because of its morals, though, for the word of God is still a word, and it appears conveniently to have been written in the language of man, and when has that ever saved anybody? No, the Bible held the answer to this unsolved problem that his life had become in quite another way.

He opened the book to page 455. At the very top of the page, he could now see he had casually stumbled upon Jeremiah 29:11. Strangely enough, it was the first time he had actually bothered to see what was there.

It did not disappoint:

‘For I know the thoughts that I think toward you, says the Lord, thoughts of peace and not of evil, to give you a future and a hope.’

It was nice to see that God still retained that characteristic sense of humour of his which so endeared him to the Egyptians (hurling the Red Sea at them, talk about a practical joke). But how could it be that he had chanced upon a quote about hope of all things? It was particularly striking, especially when one considered that starting on the next page he had hollowed out a section of the book, and therein was the actual answer: a pistol.

The juxtaposition of hope and despair was artistically right, if nothing else in his life had been for the last five years. He of course had not planned it; he had merely opened the tome at random and stabbed at it with a knife a few years ago, not knowing he was going to chance on that particular verse. God is veritably in the details; the coincidence indeed betrayed intelligent design, this, at any rate, proved it: in the world there are miracles, they just happened to be black, to be irrelevant, to be almost insulting really.

He dropped the Bible to the floor just like in a minute the pistol itself would drop the shell casing of a bullet, just like his soul would drop the flesh casing of his spirit. He walked towards the bathroom and climbed inside the tub, pistol in hand, thinking how he was at last ready not to have to make this choice again, not to have to pull the trigger ever again. According to his watch it was 7 pm. According to everything else, it was a nightmare, and it was time to wake up.

How can death be so completely strange, so foreign, how does it have this absolute otherness to it when it is something we all experience, when it is one of the few universals in this world? Well, it doesn’t. Not when it is one who actually experiences it; if he had died instead of her, he perhaps would not have complained… it was the fact that she was gone…

He never got over her loss, maybe because he never tried to. When one spends most of one’s time in memory, when is it that one really lives? The year in which the remembrance takes place, or the year that’s being remembered? For a coma patient, what is reality? A dingy hospital room or that dark forever of eternal dreams? When one spends most of one’s time in memory, what is time?

Losing someone you love is more than just losing a person, for something else is ripped from you by an impassive, passive destiny: you lose the world, a great crack opens under your feet, but you also lose the moments you would have had with them, the laughter, the caresses, the future opportunity to apologise to them for being a human being, which is a crime few of us have escaped, you lose time with them, time you never had, but could have, you lose the possibility of time, the possibility of a future… What does it mean to live? What is it to have a child? To be born? A gift of life, which is a gift of death. C’est la vie, c’est la vide: a journey from nothingness to nothingness, with a stop and a change of trains along the way. The only difference is the direction, somethingwards to nothingwards. There is a perfect symmetry to it, he supposed. It’s the rhymes that give it away, that betray God’s design, God’s treacherous design… life, death, cemetery, symmetry.

He held the pistol’s muzzle to his head. Outside there was a bed shrieking, constantly smashing itself against the window pane. In his mad fancy, he envisioned it felt the desperation of the soothsayer that tried to warn Caesar about his imminent murder without being able to make himself heard.

But this was different, when the victim and the murderer are the same, no warning may change their resolve. Except… Oh, that dark, gaping abyss of cycloptically threatening him with a bullet, that perfect circle of Cimmerian oblivion inside the gun’s muzzle reminded him of her impossibly dark pupils…

The day she disappeared, over five years before the present nightmare, they had had a fight; there had been little reason to it, save that Fate often conspires, almost as a matter of principle really, to make people leave us forever at the worst possible moment, just when we are angry at them, just when our ‘I love you’ is replaced by the slamming of a door as we storm out in a rage. But being in love is mostly all about crying the word ‘love’ as scornfully as one can manage, often at the heavens, often while being lapidated by the rain. Oh, the rain, the rain, they had first made love while it was raining…

In many ways, losing her felt like losing his faith and then suddenly finding out there was a God, but not a forgiving one, not a particularly benign one, but a sadist with a thunderbolt. Though, at this point in the tragedy, he rather inclined to the view of divinity held by the Hindus; for their Shiva has more than four arms, and the way his life had turned out that was the absolute minimum to accommodate for the number of thunderbolts that had been incessantly and pitilessly hurled at him. That was the only way to explain the hell in which he had lived for the last five years.

But not all is lost: no matter how bad things get, we still retain our ability to suffer. That never leaves us, and there is some comfort to be had in that consistency.

He placed the gun’s muzzle inside his mouth; a taste of metal reminded him of that time they had kissed each other so much, so long, so lovingly, that a single drop of blood had landed on his tongue.

Love itself is rigged.

He had half guessed it in the moments of abstraction and ennui that one invariably experiences when sitting out on the terrace of a café in Paris; spleen might very well be on the menu everywhere, it might very well be the national dish, because that is what one gets every occasion when, as a bachelor, one looks over the rim of a cup of coffee at young couples having their promenades through the city, walking hand in hand and engaging in all the lies that they must tell each other and themselves in order to keep loving.

Back then, before meeting her, he had half suspected that he was to be forever alone, outliving everyone and eternally wandering the sand wastes until the eons themselves succumbed to the forces of entropy. Now, talk about romantic prospects, there are no sand wastes in Paris.

In those days, he had been in a committed relationship with Erato (the muse of love poetry), so no, he was not looking for something serious at the moment. And yet he would sit on a bench by the park and watch young demoiselles walk by trying very hard to make their bonnets look fashionable, and he would write sonnets to them; but there was a bit of problem with all this; for, fourteen lines later, he would be more in love with the poem than the girl in question, which is, perhaps, not the desired result. When the work of art surpasses the muse, that implies that the whole theological hierarchy has been turned on its head. This was not entirely bad, however; indeed, dying alone seemed like the perfect way to stay in love with the idea of love.

A compromise had to be made: he would die alone and disenchanted…

Oh, if only he had never met her, but no; instead, she had forced herself into his life, with her charm, with her grace, with her intelligence and her absolute loveliness, her horrible, horrible loveliness, and so, instead of loving love, he fell into it, fell into her (for what is a lover, but an abyss?), and, as he fell at breakneck speed, he was able to note quite personally, that love is remarkably like a bottomless well, for you never stop falling. The crash won’t kill you, but the doubts might.

But then something even more horrifying happened, for he was thrown out of love, against his own will and hers, thrown out of love as though it were a hot-air balloon at a gut-wrenching height. He had landed, we all do, but he had survived, and that was indeed the problem; for, now he finally understood it, love is rigged.

There is no way in which it can triumph, no matter what you do, no matter how much you care for your sweetheart, you are destined, predestined, rather, as in some horrifying Greek tragedy with none of the art, none of the morality, but all of the brutality, to hurt them, to break their heart, to make them know a kind of suffering that seems almost inhuman in scope, but that is the crowing privilege of being a human being.

He cocked the pistol.

It is indeed quite strange, in most cases, a heart is broken because it goes unnoticed. We simply bump into it, accidentally knocking it from its pedestal as though it were a rich vase; or we step onto it without meaning to, like it was an ant. In such matters, there’s always recrimination to soothe one, ‘how could you do this to me’ and so on, and so forth; and the other person invariably replies ‘so sorry, was that yours? I didn’t see that.’ Nevertheless, when it is Death that rips away your loved one, when he dooms or woos her from under your mortality, you don’t even get a chance to blame anything but their mortality, their vulnerability, their humanity; and was not that why you loved them in the first place?

But then again, we should have known, of course, us more than anyone, because Paris is the city of love, and French is the language of love, and it is already the nineteenth century, so someone really should have noticed the phonetic resemblance between ‘c’est l’amour’ and ‘c’est la mort’, because now he could guarantee it was not a mere coincidence. Perhaps another of God’s practical jokes?

Words are, of course, a trap, for they make us believe we can grapple with reality, the way he was grappling with this pistol. But saying the word ‘love’ doesn’t mean you understand it, it doesn’t mean you understand anything. You can shoot a gun, but you could probably not build one. Nevertheless, sometimes we can use words to reveal relationships between these traps of language. L’amour, la mort, is only the most recent in the endless list of unsolved mysteries and miseries. Here’s another one: every creature who makes use of language will languish; delightful, is it not? Living only to die? Speaking only to end up mute? Loving only to lose the ability to love, which was what made life worth living? Naturally, words being what they are, to open oneself emotionally by means of them is but to open up in the same manner in which a bear trap displays its iron jaws: we expose ourselves with the express intention of closing down on someone and crushing them into us. That’s what we all want really, to trap our lovers inside us.

But it cannot be done.

Love is rigged. Even if you manage to live happily with your lover, Death will come between the two of you one day. And it will be impossible for one of the pair, the weakest, not morally, but physically, humanly, to refuse its advances, because it has more money, and a better job, and a nicer hearse. Two scenarios unfold, either she dies making you the most miserable man on Earth, or you do and your last act on this Earth was to make the person you loved the most drown in pain.

Maybe that’s why she left, if left she did. To spare him the agony of her death? Could it be? Household pets sometimes run away when they sense the end is near, not to put their owners through the ordeal of watching them die. Human beings seldom do that, because they lack the humanity of cats, perhaps… One does wonder… if everything is against us from the very start, why we bother to fall in love? He could only think of two answers.

One: it is worth it, despite the pain, the sorrow, the woe, the wailing, the promises never to do it again.

Two: we do not choose it at all and have as much agency in selecting our doom as a moth flying into a searing light.

A poem she had read to him a few years ago on the nature of love came to mind. It was a sonnet by the illustrious M Ian Charles Lepine, whom Iphigénie deemed the brightest artistic mind of the century. He himself had his reservations about such pronouncements, but the sonnet per se was, as anyone possessing any taste, or the least screed of artistic judgment would assert, beyond lyrical reproach:

‘There is no wisdom but to be in love,

And welcome open-armed its precious folly

That makes one negligent of what’s above,

What one should do or what consider holy.

There is no wisdom but renouncing knowledge,

And, in agreement of love’s labyrinth,

Render ourselves by freedom into bondage,

And seek in tears a scent of hyacinth.

There is no pleasure but to seek our pain

From those who make it that we drown in dew;

For what is love, but fresh, and acid rain,

Which burns and cools alike? What shall we do?

If we are all condemned to feel its stings,

Let us drink poison from the clearest springs.’

Love is indeed a death sentence, but we get to choose our poison, which is the only reason why we bother having free will at all. The complication is not the present: the real problem is having had free will, having been born in the first place, having had to choose between choosing and not choosing.

Sometimes he wished he had never met her, even though this pain was just a testament to the joy he experienced five years ago. But bliss in the past cannot hold a candle to woe in the moment. It’s all a chemical reaction really, like trees turn carbon dioxide into oxygen, so does death turn joy into misery. It’s but the residue, the waste matter of happiness. And like with carbon dioxide, one can die from breathing it too long.

But maybe that’s the purpose of grief, the reason why it happens in the first place: to make loss matter, to make it irrevocable. Because dying and not being born in the first place are very similar states to the person who leaves; but not to the one who stays behind.

Even though he would never give her up, not one second, not one locket, not one lock of hair, he wished none of it had been real, that none of it had happened. He wished it all were a lie, a novel, most of the benefits and none of the drawbacks of actually being alive, being able to remember her, but only as a literary character; someone who was fundamental in the creation of his own personality, but the perdition of whom did not constitute a tragedy in real life; someone whom maybe he even loved, in that certain abstract way we sometimes have, but whose demise was not catastrophic, because, as some friend had told him (back when he had friend) whenever their literary discussions became too agitated, ‘literary characters are not real.’ He wished she had not been real… Although… well, who amongst us can actually claim to be real? You go to any building in Paris where more than two people are currently in the same room at the same time, and it will be fundamentally filled with lies. That, instead or water, is the main element whereof human beings are comprised.

He wished he hadn’t seen here there and then, that first, fatal, fated, day when they met. For she looked so beautiful, seating on a flower-print chair in a sumptuous parlour, with the light caressing her as if the Sun God himself had claimed her for his love; the sunbeams that fell on her had made her skin glow into a mysterious—nay, a miraculous white; they had taken all the colour of her, stripped it from her features like the ages pried away the pigments of multi-coloured gaudiness from Greek sculptures. The past is always idealised. It’s almost too crass a subject to discuss in polite society, but, the ancients would paint their works of art in the most astoundingly tacky and meretricious hues. Indeed, if time had not destroyed those pigments, we would have thought twice about making the Greeks the cornerstone of our civilisation. The impression of white, gleaming marble we have of the 5th century BCE, and indeed, most of Antiquity itself is, of course, a modern invention.

Maybe this memory he had of her then, crowned by a halo of light that did not stop at her head but surrounded her whole body (for there was no part of her that wasn’t divine), was also a fabrication of his fancy; for, now that he thought about it, Iphigénie had indeed looked to him like a marble statue, which is rather improbable.

She sat in the couch in front of him, not speaking, staring straight at him, not moving one inch, one eyelid, one muscle, one particle of her static wonders; and meanwhile he could only think of how beautiful she was, of how much he wanted to kiss her and touch her; but something forbad him to do it, and it was not only the rules of engagement in the conflict of love, the ungentlemanly code in the war of attrition that is courting a girl, or the etiquette of commingling in polite society (which is very much the same thing as the other two), but something much deeper, and it was the same reason for which one does not touch the Vénus de Milo at Le Louvre: for she was art, for she was above it all, not really of this earth, and he wouldn’t dare profane her pentelic skin with his touch.

The Way of Saint James is perhaps Europe’s most renowned pilgrimage; it has a history going back to the early Middle Ages, and it is a path that takes people from the very cliffs of desperation unto the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Some pilgrims completed it while crawling on their hands and knees, as though, as human beings, we weren’t doing that already in our own, bipedal way. Presumably, this trek will fix everything; some may undertake it because they suffer from disease or despair, which is but a disease of the soul, and they think that perhaps a miracle will cure them; the real miracle, of course, is that people are actually willing to do such an absurd thing as this. The miracle was within them the whole time! Again, God’s idea of a sense of humour.

The pilgrimage ends at the cathedral, when the devout kiss the foot of the Apostle St James. Naturally, the foot of the statue is in a bad way now, for the kisses it has received have damaged it irreparably, mainly because humanity erodes divinity.

It was just like that with her… He was afraid of touching her, because if he damaged her, the loss would be irreparable, as she was holier than the statue of a dead man, for she was a living miracle. But loving another human being is diminishing them. Each time you kiss someone, you plane a little of their personality away, every gesture of love is like hitting a marble statue with a chisel, for you try to leave your mark on it, to make it yours. And if you love too much, you will break them. She was a work of art, of course, but if he couldn’t not touch her, he at least wanted to own the copyright. And the only way to do that was to make her his. The problem was that she was already her own, that she was already made; what could he do then, to have a hand in the fashioning of her lovely self? Only but to help her grow, to collaborate on the creation of her own masterpiece, to share authorship of her person with her person.

Still, his first impression of her had been that she was not real, not flesh and bone but alabaster and ivory. He felt what Pygmalion must have experienced before Galatea had been doomed with life… And now, now that she had been doomed with death, who could commiserate with this pain? If Pygmalion had accidentally knocked Galatea off her dais, and had seen her break on the floor, would he have found amongst her fragments the pieces of his own shattered heart?

He was about to pull the trigger when he remembered something. It was perhaps not transcendental, but it seemed so vitally important that he simply could not go through with it; he simply could not kill himself; not until his doubt was resolved. Ignorance is of this world, we must not take it to the other one.

Just like someone may wake up in the middle of the night to look up the etymology of a word in a dictionary because not knowing will not allow him to consign sleep, in that same manner, he stopped himself from jumping off the cliff of life. This was the question: the Spanish call the apostle Santiago. We call him St Jacques. The English call him St James. But it is the same person. Why is that? He couldn’t go to the great beyond with that doubt in his mind; it would be irresponsible, he would be all cross in the afterlife. We know nothing about death, but it is safe to assume that the reference section in the public library is probably not very thorough. And etymology is at the root of all of us, it only made sense to make it the root of his death as well.

He climbed out of the bathtub, gun still in hand, and walked back to the bookshelf, from which he produced his always reliable Larouse Dictionary of First Names. Say what you want about the French, but even the poor often have a decent reference section at home. You couldn’t say that about the English.

Jaime, Jakob, Jamal… there it is, James! ‘The name of two of Christ’s disciples in the New Testament: James, son of Zebedee and James, son of Alphaeus. From the Late Latin Iacomus, a variation of Iacobus, from Greek Iakobos; though we often think of James and Jacob as two completely different names, they have the same etymology. See: Santiago.’

Typical of these things to make you hunt down information through several parts of the book as though as though it were an exotic bird instead of just giving it to you right there and then… Then again, he was in no particular rush, for Charon’s ferry did not leave until midnight. And missing it wouldn’t kill him, not precisely.

He leafed through the second half of the dictionary.

Sabina, Sandalio… Santiago. ‘Literally Saint James. Iago is an archaic Spanish form of the name Jacobus.’

Well, that, at any rate, was that. He scratched his head with the muzzle of the gin. Saint-Iago, Iago, Iacko, Jacques, James. What a strange world. Santiago, Jacques, and James: three names to a single body, linguistic triplets if he ever saw them. What a strange world, pity he was going to leave it behind.

He started walking back into the bathroom.

For many, The Way of Saint James ends at the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. But there is a further stop, for the really devout. Cape Finisterre in Costa da Morte. In Roman times it was believed to be the end of the Earth, hence the name; and it was only appropriate that it should be placed in the Coast of Death, a passage renowned for its treacherous waters that have caused myriad shipwrecks in history.

He climbed back inside the tub and put the gun into his mouth.

Tradition dictates that, after kissing the granite foot in Compostela, a pilgrim is to walk the ninety kilometres that separate the cathedral from Costa da Morte. When he arrives at Finisterre, he is to burn his clothes to signify he has achieved purity.

He had done something more extraordinary: he had kissed not a statue, but a miracle, and now he was going to powder burn not his clothes but his entire mortal coil. His only regret was that, he would not die with her kiss upon his lips; Death would be the last lover he knew.

He pulled the trigger.